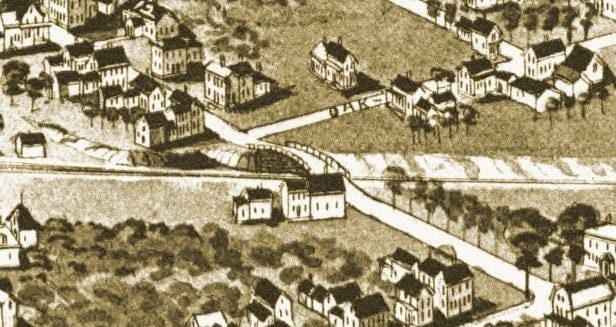

The 1884 Birdseye Map of Exeter showing the Park Street bridge. USA Today Network

Charles Bell, Exeter historian, says of Park Street, “This was for a hundred and fifty years one of the main avenues to the water side; and over it was transported a large proportion of the original growth of the forests which covered many square miles of the old township.”

In Exeter’s early lumber days, the street ran from the shipyards on the Squamscott River directly to Epping Road.

After the Revolutionary War, the lumber and shipbuilding industries sank as local forests were depleted. The little street, however, continued to be a useful road. It appears as “Lane’s End” on the 1802 map of Exeter, and this may have been its original name.

In 1835, a charter was granted by the New Hampshire legislature to the Boston and Maine Railroad to extend a line from Boston to Portland. In Exeter, the line would need to cross Front Street, Main (then called Middle) Street, Park Street and Newmarket Road (now called Newfields Road). Front Street was designated as the depot, so the crossing there would be at ground level. Middle Street would likewise have a ground crossing with a manned gate. Both Park Street and Newfields Road would have bridges instead, with the train running beneath the Park Street bridge and on top of the Newfields Bridge. Chief engineer James Hayward hired Asa Sheldon to do the stonework abutments of both bridges in late 1839. He called the Park Street bridge “Furnald’s Bridge” as it was located near the land of retired sea captain Joseph Furnald. Sheldon later wrote, “After a while, Hayward, the engineer, came and said to me, ‘How soon can you be at Exeter, ready to work at Capt. Fernald’s bridge?’

‘How soon do you want me if I could be there?’

‘I want you to be there very much tomorrow morning at eight o’clock.’

‘I think I can be there at that time,’ I replied.

We loaded our stone tools and set out at midnight; travelled fourteen miles before sunrise; stopped and breakfasted at Dodge’s tavern, and proceeded to the ground and were ready there at eight o’clock.”

His account of meeting Captain Furnald, along with his assessment of the job (“This bridge was finished without any special trouble”) and the lack of any delay, indicates that it was finished by the time the train arrived in June of 1840. The bridge was considered a safer and less expensive way of crossing the tracks with no gatekeeper to pay.

In 1890, the Boston and Maine upgraded their tracks, and its Exeter bridges were too narrow. The Newfields Road bridge was rebuilt and widened, but the railroad balked at the cost of replacing the Park Street bridge. The street was closed in January of 1892, and the bridge was torn down to extend three full lines of tracks across Park Street.

Arguments with the town soon arose over whether it should be a grade-level crossing or a rebuilt bridge. The bridge would need to be higher than the old one – trains having grown taller since 1840. There would need to be crossing gates with a paid gatekeeper. The arguments went back and forth for several months in the time leading up to Exeter’s town meeting.

One voter wrote to the Exeter News-Letter, “it would be easy for the railroad to run over instead of under the street. The public would need a wide but not very high carriage way under the railroad.” Another complained that unforeseen costs would arise if the street was closed permanently, from the Park Street residents’ lawsuits, and possibly a new school needing to be erected. “Now who is to pay for all this? Certainly not the railroad, for the town of Exeter, by voting to discontinue the street will take upon itself the responsibility, thereby freeing the railroad company.”

There was even a bit of misinformation tossed at the public: “When the rails were first laid, fifty or more years ago, they were at grade across Park Street without objection or opposition. At that time, many more in numbers, and some of them very young in years, attended school in the brick schoolhouse than now. A few years thereafter, parents having anxiety as to their safety in crossing the track, through their anxiety application was made to the then directors of the road to build the bridge over the track on Park Street, and with the influence of the selectmen, the bridge was built and was satisfactory to the authorities.”

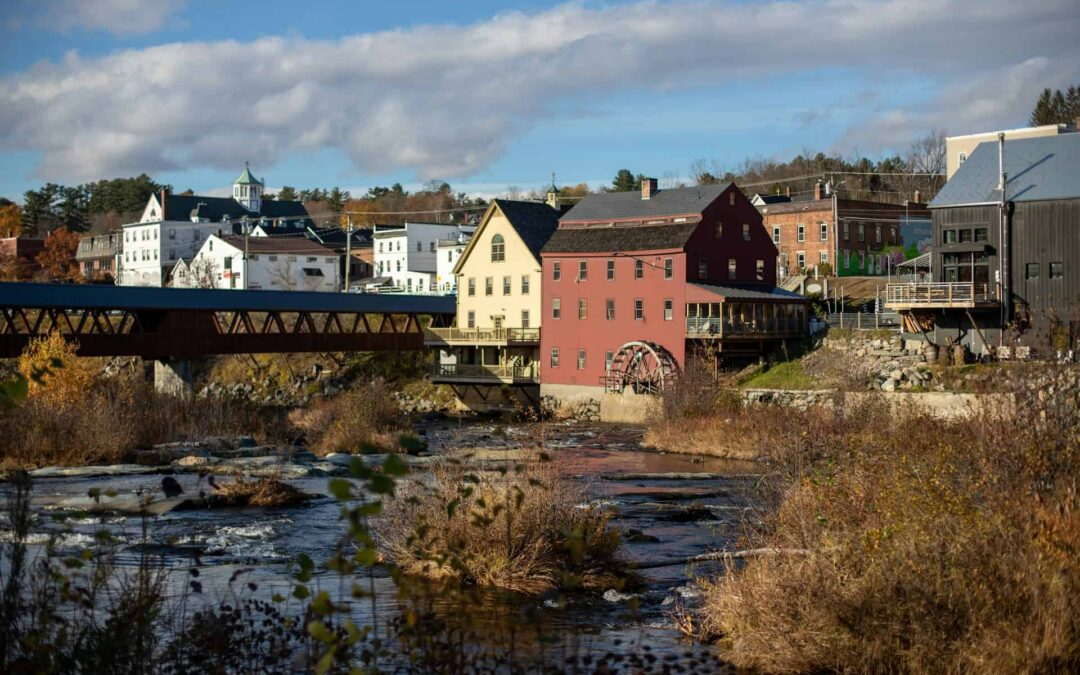

At the town meeting, it was determined that the town would approve a crossing at grade level. However, the Boston and Maine decided to go ahead with the bridge anyway, as new regulations were going to strictly limit the number of grade-level crossings. Stonework was laid in April. In July, the News-Letter reported, “A gang of men from the Springfield, Mass., Iron Works is putting the new Park Street bridge in position. The structure is a substantial iron truss bridge, with a roadbed twenty feet wide. On the south or depot side is a walk for pedestrians five feet wide. The iron work will be completed on Saturday, after which the planking will be done by the railroad company.”

The bridge was open to the public on August 12, 1892, to all but one man – Edward Valentine Gilman. “One abutter, Mr. E.V. Gilman,” the paper reported, “is without means of leaving his premises, and the question of damages may go to the courts.” The dispute did not last long, however. Gilman sold his house and property to the B&M, although he reserved the right to move his hen house within 90 days of sale.

Barbara Rimkunas is the curator of the Exeter Historical Society. Support the Exeter Historical Society by becoming a member. Join online at www.exeterhistory.org.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald. Reporting by Barbara Rimkunas / Portsmouth Herald.

We asked, you answered: Who should be president in 2028?

A version of this story appeared in the Granite Post's newsletter. Subscribe here. The 2028 presidential race may feel far off, but early polls are...

How early is too early to put up Christmas lights? What New Hampshire laws say

Halloween has come and gone – so is it time to put up the Christmas lights? Every year, debate swirls over how early people can start putting up...

All the ski resorts in New Hampshire + their projected opening dates

Ready to hit the slopes? Discover when all of New Hampshire’s ski resorts open up for the 2025-2026 season. New Hampshire is home to numerous ski...

Bestselling cars in New Hampshire

As luxury-brand vehicles continue to swell the market, the average price for a new car in the U.S. has modestly declined, signaling an increased...

3 charming New Hampshire Towns that are straight of storybooks

From Uncle Sam’s house to covered bridges, these three New Hampshire towns have charm to spare. Anybody who has seen a Hallmark movie set in a...

8 TV shows set in New Hampshire to add to your watch list

From animated series to hit shows, several TV programs have been set in New Hampshire over the decades. Here are some of the most intriguing. For...