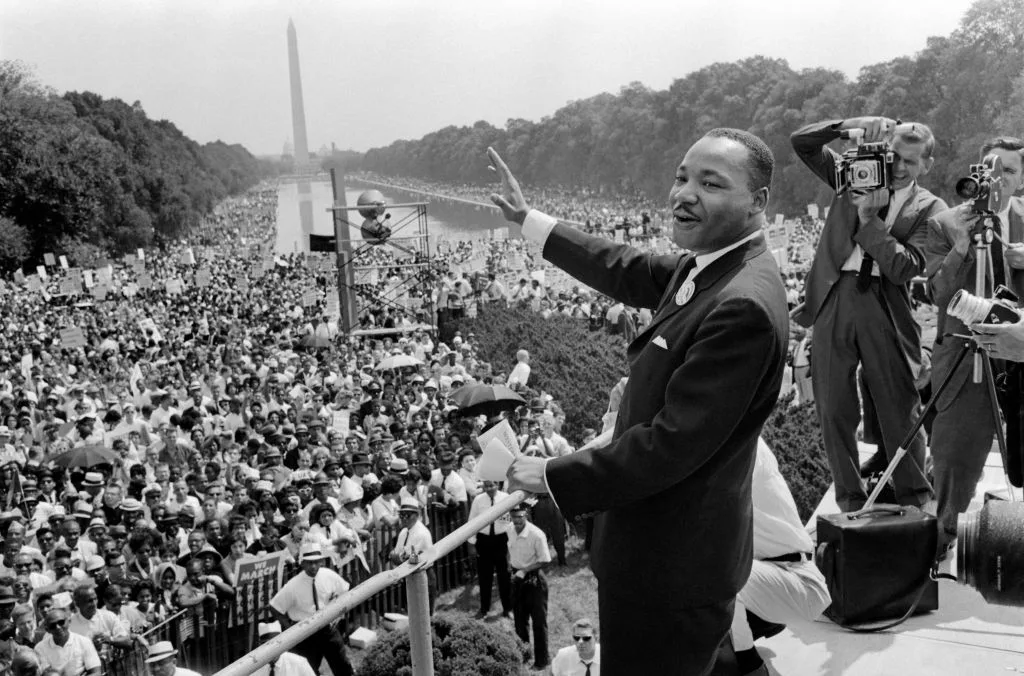

Martin Luther King waves to supporters August 1963 on the Mall in Washington, D.C. (Washington Monument in background) during the "March on Washington", where King delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. Photo by AFP via Getty Images.

After Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1968 assassination, calls for a holiday in his honor took root. In 1983, Coretta Scott King advocated for celebrations on her late husband’s Jan. 15 birthday. President Reagan declared it a federal holiday, with many states following suit.

But, not New Hampshire.

The state was one of the last, along with Utah and South Carolina, to celebrate Martin Luther King Day. It took 20 years, a grassroots campaign of thousands of people, threats from businesses to boycott, and nearly a dozen failed bills before it was finally celebrated for the first time on Jan. 17, 2000.

“It was embarrassing to be a member of a Legislature that simply would not honor Dr. King,” said Peter Burling, the Democratic leader at the time.

Those involved in the law’s passage back then said the struggle makes the holiday more meaningful now.

“We got there because of hard work, patience, and just determination,” Burling said. “We weren’t going to take ‘no’ for an answer again.”

Those involved remember the cohort of people—the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the state’s largest manufacturing company, Digital Equipment Corporation, banded together. Students walked out of classrooms and Portsmouth residents barred cold days and nights to march from the New Hope Baptist Church on Pearl Street to Market Square in protest.

“It took people rising up and saying, ‘this is important to us,’” said Arnie Alpert, the former director of American Friends Service Committee. “We didn’t give up.”

Alpert remembers rallying people by stuffing envelopes and using phone trees.

“It was a different time,” Alpert said. “The work was done by sending out mimeograph or photocopied newsletters in the mail, creating suggestions for talking points, and reporting common arguments that were being made against the King holiday.”

Alpert’s persistence, he said, was inspired by King himself.

“I began to see Dr. King’s approach to organizing as an approach I could use myself, not only to win passage of a holiday, but to win passage of a higher minimum wage, to win civil rights for immigrants in New Hampshire, to end the death penalty in New Hampshire,” Alpert said. “In all those campaigns, Dr. King’s example, and Dr. King’s philosophy, and Dr. King’s life became guiding lights for me.”

The history

Sen. Jim Splaine first introduced the bill in 1979. After it failed, he introduced similar bills again and again.

Splaine, who at 21 years old became the youngest person ever elected to the New Hampshire Legislature in 1968, was used to adversity.

“I knew there would be intense opposition, because it was such a national issue—divisive but unifying nevertheless,” Splaine said.

After years of debate, lawmakers in New Hampshire created Civil Rights Day on the third Monday in January in 1991—a compromise.

A bill that year to include King’s name on the holiday passed the state Senate, but failed in the House. The Senate agreed to the House version, which excluded King’s name.

Opponents claimed the small Black population in New Hampshire, about 1%, diminished the bill’s urgency. Opposition also stemmed from King’s stance against the Vietnam War. Some called King a womanizer, some called him communist. The Union Leader, one of the state’s most influential media organizations at the time, campaigned against a Martin Luther King holiday through editorials.

“It was hard,” said Ray Buckley, who chairs the New Hampshire Democratic Party. “There was never any honest answer from those opposing it, other than he didn’t deserve it. I don’t think they were being completely honest or up front about their blatant racism.”

Burt Cohen, a former Democratic state senator, compared the sentiments back then to the rhetoric today.

“I think a lot of it has to do with what’s still going on in the United States,” he said. There are people who want white supremacy. They can hide behind all different arguments—that (King) was a communist, that he was a womanizer, but that’s obfuscating the reality.”

Jackie Weatherspoon, who was the third Black woman elected in New Hampshire and the only Black female state representative at the time, was the lead on the House bill.

Weatherspoon credits a group of women at the time who came together to ask businesses to boycott New Hampshire—similar to efforts in Arizona.

Arizona’s controversial holdout on recognizing Martin Luther King Day cost the state its first super bowl—Super Bowl XXVII—in 1993. Arizona lost an estimated $200 million worth of economic impact, the Associated Press reported in 1990.

“It was such a different time,” Weatherspoon said, pointing to blatant racism and sexism in the Legislature and lack of understanding. “As a Black woman I couldn’t even wear braids.”

Weatherspoon, who is from North Carolina, lives in Exeter now, where her husband Russell is the dean of Phillips Exeter Academy.

Weatherspoon was a senior in high school when both Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. were assassinated.

“I was like, ‘why are all these people who are working for justice getting assassinated?’” she said.

At the time, she said she was too young to understand what justice was, “but I knew what death was.”

Weatherspoon, who decided to run for office in New Hampshire after attending a women’s conference in Beijing, was inspired by what King represented. He defied the odds of his time. King had a doctorate in philosophy from Boston University. His wife attended the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston.

“We’d never celebrated an African American on a national level,” she said, and believed, “This is the man we should do it with. To me it was the culmination of so much history that I had lived through.”

The shift

The change in thought happened gradually.

“I think in all of society, there is ongoing resistance to the deep work of transformational change,” said Maggie Fogarty, the program director of American Friends Service Committee.

“What ultimately led to (Martin Luther King Day) being passed was a growing consensus among diverse segments of the New Hampshire society that we wanted to aspire to Dr. King’s vision and practice.”

Democratic Gov. Jeanne Shaheen was influential at the time.

When Shaheen took office in 1997, she issued a proclamation in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr. Civil Rights Day. The proclamation referred to King as “the preeminent leader of the civil rights movement,” and compared his beliefs to New Hampshire’s “Live Free or Die” spirit.

Shaheen’s inaugural speech in 1998 again urged the Legislature: “We must not end this century without marking Martin Luther King Day part of the heritage we leave to our children,” Shaheen said in the speech.

A bill passed the Senate that year, but failed in the House by just one vote, 178-177. It wasn’t until 1999 when the bills passed both chambers.

Shaheen, now a U.S. senator, grew up in Missouri, where she remembers attending segregated public schools with separate drinking fountains and restrooms. She later became a teacher at the first integrated school in Mississippi. When she took office in New Hampshire, establishing a King holiday became a priority.

“When we finally got it done, I thought about how far we had come, and how it represented the type of resilience Dr. King’s movement inspired,” Shaheen told the Granite Post in an email.

The signing

The bill was signed on June 7, 1999. Shaheen held a rally on the front steps of the State House that day and Martin Luther King III joined the governor under a warm, early summer sun.

It was a defining moment for those involved.

“The bill signing was one of the best days I had in my 18 years in the Legislature,” Buckley said.

King’s “I have a Dream Speech” has a line that mentions New Hampshire. It says, “Let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire.”

The people of New Hampshire responded by ringing bells as the bill was signed, “So let freedom ring,” Buckley said.

The first thing Weatherspoon did the day it passed was call her kids and say,” This is part of your legacy, too,” she said. Her four children’s last name would always be on the bill.

“It was such a historical thing for Black people not only here, but all over the world,” Weatherspoon said.

The legacy of King’s work continues for Alpert. In King’s spirit, Alpert looks at what’s going on around him and thinks of what he can do to bring about change in his lifetime.

Alpert follows these steps: “Understand what the issues are, educate yourself, educate the community, try to negotiate with the people who are in power,” he said. “When they refuse to budge, that’s when nonviolent direct action becomes important and perhaps essential.”

Then, “Always aim for what King called in the end, ‘a beloved community’—a place where we can all agree, a place where everybody is uplifted, and not simply winning over or being victorious over somebody else,” Alpert said.

Corretta King sent a note to the New Hampshire organizers, including Alpert, shortly after the bill passed.

“We are all much inspired by your tireless commitment,” Coretta wrote in a copy of the note obtained by the Granite Post. “I have no doubt that your creative and unrelenting dedication to the New Hampshire King holiday coalition was critical to the success of this legislation, and I commend you and all of your supporters for keeping the spirit of nonviolence at the center of your efforts.”

Support Our Cause

Thank you for taking the time to read our work. Before you go, we hope you'll consider supporting our values-driven journalism, which has always strived to make clear what's really at stake for New Hampshirites and our future.

Since day one, our goal here at Granite Post has always been to empower people across the state with fact-based news and information. We believe that when people are armed with knowledge about what's happening in their local, state, and federal governments—including who is working on their behalf and who is actively trying to block efforts aimed at improving the daily lives of Granite State families—they will be inspired to become civically engaged.

Bestselling cars in New Hampshire

As luxury-brand vehicles continue to swell the market, the average price for a new car in the U.S. has modestly declined, signaling an increased...

3 charming New Hampshire Towns that are straight of storybooks

From Uncle Sam’s house to covered bridges, these three New Hampshire towns have charm to spare. Anybody who has seen a Hallmark movie set in a...

8 TV shows set in New Hampshire to add to your watch list

From animated series to hit shows, several TV programs have been set in New Hampshire over the decades. Here are some of the most intriguing. For...

6 reasons why New Hampshire was ranked the top Halloween state

New Hampshire is famous for autumn weather, but did you know it’s a top state for Halloween? Read on to learn why it’s a “spirited” seasonal spot. ...

‘Welcome to Derry’ based on Stephen King’s ‘It’ comes to HBO in October. How to watch

If you've ever seen the film, "IT," or read the book by Stephen King, you know that Pennywise the clown is a horrifying creature. But people can't...

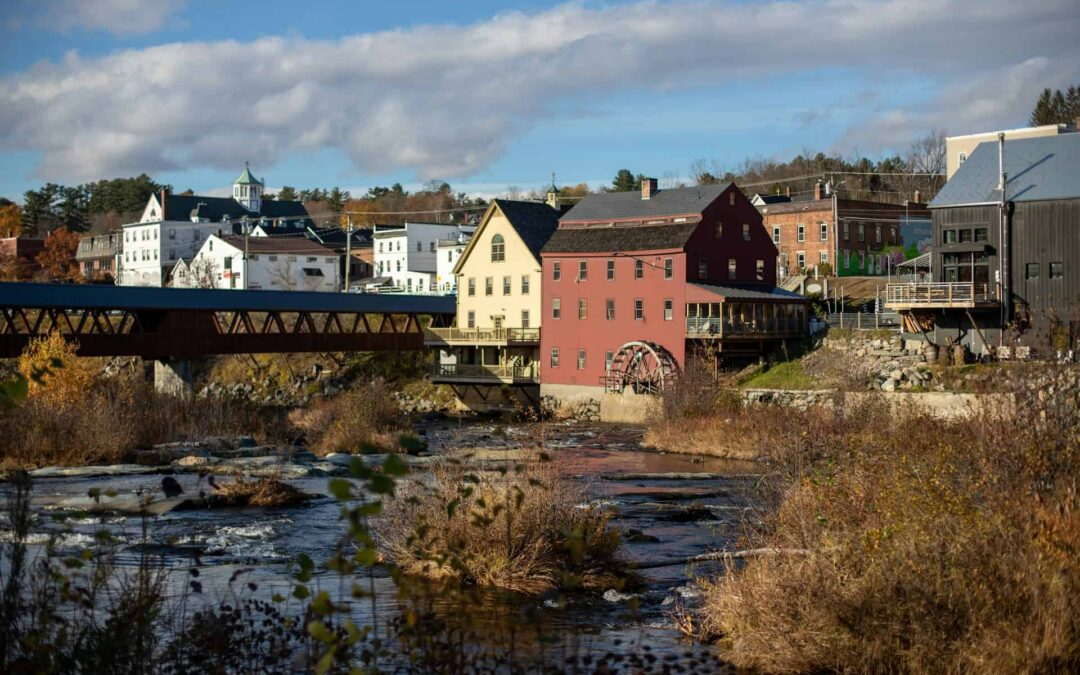

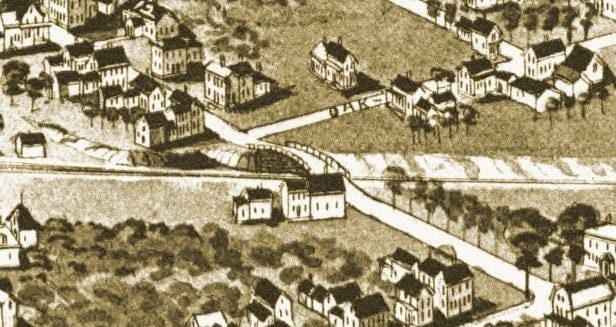

Historically Speaking: The story behind Exeter’s Park Street Railroad Bridge

Charles Bell, Exeter historian, says of Park Street, “This was for a hundred and fifty years one of the main avenues to the water side; and over it...